Mumbai: The Indian Film Festival in the German city of Stuttgart is taking place this week with live audiences for the first time since 2019. Until 2011 the festival was actually called "Bollywood & Beyond" but the name was dropped because Indian cinema is so much more than mainstream Hindi-language movies.

"Bollywood" is a compound of the terms Bombay (the old name of the city of Mumbai) and Hollywood. A film critic invented the word crossover in the 1970s to make one of the world's most successful movie industries more palatable to Western audiences.

Bollywood also stands for films made in the Hindi language, as opposed to India's other 120-odd tongues including Urdu, Malayalam, Tamil, Sanskrit and Bengali — some of which also have their own film industry.

Largest number of films worldwide

India produces more films than any other country worldwide, with Hindi-language films most strongly represented among the more than 1,000 productions a year. The Indian film industry generates nearly $2 billion (€1.9 billion) a year. US productions that set standards elsewhere in the world traditionally have little influence in India.

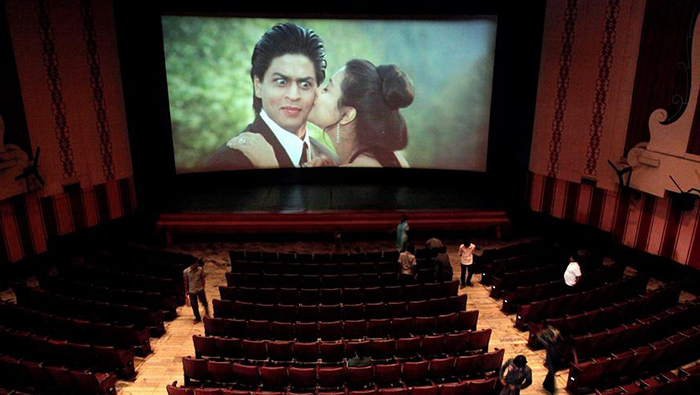

The Hindi film industry originated in Mumbai in the 1930s and had its first heyday in the 1960s and 1970s with romance films, dramas and action flicks. The movies are over three hours long and have an intermission and most feature singing and dancing.

Roller coaster ride of emotions

Over the decades, Hindi cinema developed a formula for success that includes the so-called nine rasas, or basic human emotions in traditional Indian arts — joy, fear, anger, love, courage, sadness, amazement, disgust and calmness. A Bollywood film can be a veritable roller coaster of emotions: tragedy and comedy alternate, as do action and romance. The plot is almost always about love.

Bollywoodmovies were firmly in the hands of actors who also produced the biggest blockbusters. In the 1990s and 2000s, Sha Rukh Khan, Ameer Khan and Salman Khan were the most famous outside India. Screenwriters and filmmakers had comparatively small profiles power during Bollywood's heyday.

Breakthrough in Europe

2001 was a pivotal year for Indian cinema, and for Stephan Holl, who with wife Antoinette Köster owns the Cologne-based Rapid Eye Movies film distribution company.

Fascinated with Indian cinema, they decided to distribute Indian films in Germany and Europe. At the time, that was a big risk, but the move also promoted Indian cinema beyond Asia. Rapid Eye Movies, actually an arthouse distributor, was partly responsible for a veritable Bollywood wave that took place throughout Europe a short time later.

"We brought Bollywood and Indian indie films to Germany. Bollywood had a 95% market share in India at the time," Holl told DW, adding the movies included the early films starring Shah Rukh Khan, real evergreens that people loved."

Bollywood's 'homemade crisis'

But Bollywood's recipe for successful also left a bad taste. A few superstars had too much power. There were too few female producers and directors. In addition, recurring Hindi mainstream cinema plots were becoming tired and clicheed.

In the early 2010s, box offices saw the first big flops. "What was tried and true didn't work anymore, there was a lot of uncertainty," said Stephan Holl, arguing that the crisis was homemade, and that people relied too much on the stars to fix it. He said the films were increasingly flat and formulaic.

Independent filmmakers saw an opportunity and took it.

"Suddenly there were many more female filmmakers and films without stars that had a good story and that worked, that got by on much smaller budgets," Holl said. "Arthouse filmmakers entered the scene, suddenly Indian films were showing at the Cannes Film Festival."

Anurag Kashyap, for example, is a successful Hindi language director who also produces and writes screenplays that break the Bollywood mold. His internationally acclaimed 2016 film "Raman Raghav 2.0," inspired by the serial killer of the same name, brought a darker, neo-noir edge to Indian cinema.

But does this shift mean that Bollywood mainstream films will eventually die out?

Greater cinematic diversity

Anu Singh, Indian filmmaker, award-winning journalist and screenwriter, does not see a crisis in mainstream cinema.

"Some of the biggest blockbusters have been in the last seven years," Singh told DW. It's the Covid-19 pandemic and the huge success of streaming services that are a threat to traditional mainstream Indian cinema, she argued, as well as the increasingly successful film industries of South India.

But Anu Singh sees diversification as a great opportunity for Indian cinema. "The changes have led to bold collaborations. The mainstream is opening up to other languages," she said. "Bollywood is no longer just Hindi cinema. It also means transfer to other lifestyles and adaptation. If the so-called mainstream can learn from smaller currents, it will be richer for it."

Ever-changing audience

Like Stephan Holl, Anu Singh sees the future of Bollywood in more diverse themes and casts. Currently, she said, there is still a struggle with what kind of stories filmmakers want to tell to "capture the imagination of an ever-changing audience" — an audience that is well-versed in international film thanks to streaming services.

She says she is in greater demand as a screenwriter than ever before due to a demand for new storytelling voices and perspectives.

The success of streaming services and the major changes in distribution structures are also reasons why Rapid Eye Movies has not been renting Indian films for several years.

But Stephan Holl is still a fan.

He says he watches the films — but not on Netflix. The films need a big screen, he says.

"If anything is a communal experience, it's definitely these films," he said, adding the viewing experience remains once of "celebrating [and] being swept away."